Embarking on a journey into the global workplace, I found myself faced with that familiar moment: the introduction. Working remotely, I braced myself behind my computer screen to type out those words in our common chat room, “Hello everyone, my name is Title”. It is a simple statement, yet it lies in our cultural quirks. On official documents, my name is “Chiratikan”, and I was torn between asking my colleagues to wrestle with my lengthy, tongue-twisting legal name, or settling for the simplicity of Title, no matter how awkward it might sound. I opted for the latter.

You might be curious as to why I don’t just have an English given name, right? The reason I chose not to adopt an English name to avoid any potential awkwardness stems from the cultural norm in Thailand. Generally, unless someone is of mixed Western heritage and already has a Western name, Thai people tend not to use English names.

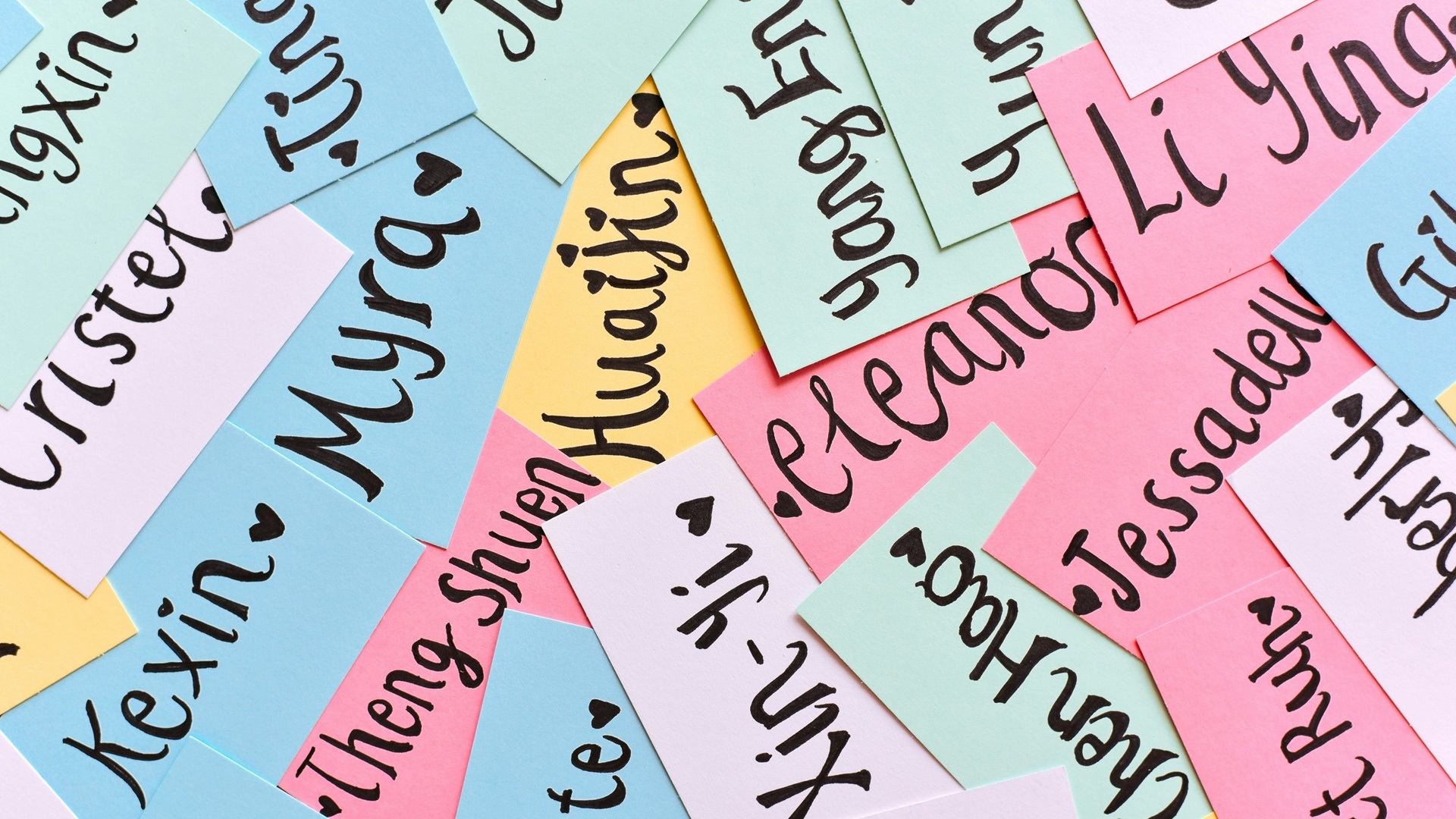

Thai people enjoy an abundance of freedom when it comes to choosing nicknames for their children. The word “Thai” literally means “Freedom” in the Thai language, and this freedom extends even to the nicknaming of their children. Unlike English-speaking countries, where diminutives like “Jenny” from “Jennifer” or “Liz” from “Elizabeth” are often linked to legal names, in Thailand, the two are distinct entities. Thai parents can nickname their children “Tangkwa” (cucumber), “Tarn” (brown), or even “Moowan” (sweet pork). In my parents’ time, nicknames were typically simple words like “Lek” (small), Yai (big), or Daeng (red). However, by the 1980s, around the time I was born, a shift occurred when families began favoring two-syllable nicknames. This trend has persisted into contemporary times. However, in recent years, there has been an emphasis on selecting nicknames imbued with a deeper meaning, like “Kondee” (a good person), “Papwad” (a painting), or “Kongkwan” (a gift).

Despite this liberty to nickname their children almost anything as their hearts desire, there are subtle rules that baffle even native Thais. Why, for instance, is it acceptable to nickname your child “Namfon” (rain) or “Mek” (a cloud), but not “Lookheb” (hail)? And let’s not forget the curious case of gender-specific nicknames, where “Namfon” tends to be reserved for girls, while “Mek” is more commonly assigned to boys. The absence of strict rules regarding gender in the Thai language, unlike languages such as German or French where nouns have specific genders, emphasizes the flexibility of Thai nicknaming traditions.

In our Thai nicknaming practices, we not only embrace Thai words but also adopt English ones, like “Title” in my case. It’s quite common to encounter Thai individuals nicknamed “Ice”, “Guitar”, “Smile”, “Gift”, “Guide”, or “Oak”. Do we care about the meaning? Hardly. We’re all about phonetic appeal rather than literal interpretations. Of course, we are aware that “Ice”, “Guitar”, and “Smile” play nice for both genders, while “Gift” tends to lean towards the ladies, leaving “Guide” and “Oak” to the gents. Can we explain why? Well, not really. Interestingly, my partner’s ex nicknamed her son “Open”, a quirky addition to our eclectic world of Thai nicknames!

Another endearing custom is the tendency for siblings, or even the whole family, to share initial nicknames. In my own household, the majority of us go by nicknames that start with “T”, from Title and Tatae to Tao, Tui, Toi, Ton, Tong, and beyond. It really shows how interconnected Thai society is.

In the whimsical world of Thai nicknaming traditions, there’s an aspect that visitors, especially those from English-speaking countries, should take note of. Some Thai words used as nicknames may unintentionally sound offensive in English due to homophones, like Porn (blessing), Fak (a gourd), Poo (a crab), or Chit (win). So, don’t be caught off guard if you encounter locals introducing themselves with these names, particularly in a workplace setting in Thailand. It’s common to use nicknames and allow coworkers to address them by these nicknames, regardless of intimacy. It’s a part of Thai culture, and it’s important to respect these nuances. After all, understanding local customs holds more significance than expecting others to change their names for the sake of convenience.

Indonesian Translation: cultureflipper.com/blog/thai-berarti-kebebasan-kami-memanggil-anak-sesuka-hati-kami